|

|

Hello

Everyone,

March

11, 2026

In

this Issue:

- The Frosty Growler

- What Really Happens to Your Heart During a Marathon

- Sudbury Rocks Running Club - Group

Runs

- Photos This Week,

- Upcoming Events:

May 24 2026 SudburyRocks!!!

|

|

| |

| March

8, 2026

CANCELLED!

|

The Frosty Growler Triathlon

is back for 2026 & bringing the heat to winter with

a one-of-a-kind challenge that mixes skiing, biking, and

running into one epic race.

Whether you’re racing solo or as a team, The Frosty

Growler is all about getting outside and embracing winter!

And.. this year, we have short and long course options!

Date: Sunday, March 8

Location: Kivi Park

CANCELLED!

|

|

|

What really happens to

your heart during a marathon

Staring down the barrel of

a marathon starting line can make your heart thump harder

than a flat tire on the highway – and that’s

before you even start moving. There’s no doubt racing

puts a lot of wear on your cardiovascular system, so is

it really safe? To answer that, check out this new story

from Outside: "What

Really Happens to Your Heart During a Marathon."

Racing causes your heart rate and blood volume per beat

to increase, raising total cardiac output by up to eight

times your resting levels. As the miles accumulate, cardiovascular

drift kicks in, meaning your heart rate tends to climb

upward to keep up with the physical demand. One finding

that surprises many runners is that troponin – a

cardiac enzyme typically associated with heart attacks

– can leak into the bloodstream during a marathon.

A recent JAMA Cardiology study found that while elevated

troponin levels are common post-race, the heart generally

recovers within days, and long-term cardiac dysfunction

is not the expected outcome for most runners. As Dr. Eamon

Duffy puts it, for the vast majority of runners, marathon

running is safe and good for cardiac health. That said,

it's worth discussing your specific situation with a doctor

before ramping up your training. Once you have that green

light, understanding your heart rate zones can help you

train smarter. This story from Polar is a solid place

to start: "Heart

Rate When Running: What is Normal?" Physical

therapist Jason Lakritz suggests that most runners can

simplify their training to three systems: aerobic (zones

1–2), lactic threshold (zone 3), and anaerobic (zones

4–5). A quick rule of thumb for gauging which zone

you're in without a monitor: if you can speak in full

sentences, you're likely in the aerobic zone; four or

five words puts you near lactic threshold; one or two

words means you're going anaerobic.

|

|

|

Sudbury Rocks Running

Club - Group Runs

|

Wednesdays

- meet at Apex Warrior parking lot departing

at 1800h. Typically runs are 1 hour or 10km.

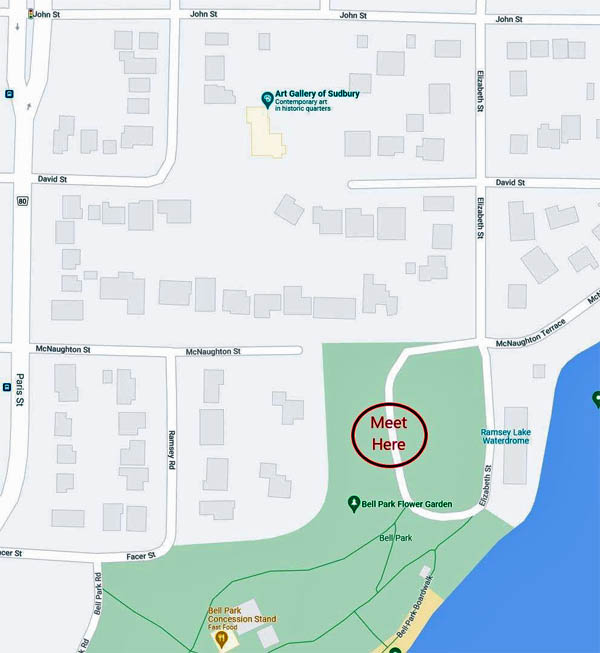

Saturdays - meet at Bell Park's

Elizabeth St parking lot departing at 0800h. Typically

runs are longer at 1.5 hours or 15km minimum.

Generally the pace floats between 5 and 7 minutes per

km. Anticipate a mixture of roads and trail running on

the routes.

Inclement weather is usually just a challenge. Group has

only been cancelled for local races or xmas. Cancellations

or changes in meeting locations will be posted.

Locations are show in the

attached photos/maps.

Wednesday pm location

Saturday am location

|

|

|

Photos This Week

March 4 Wednesday pm run

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 3 Moonlight

Mar 4 Moonlight

Mar 4 Moonlight

Mar 4 Sudaca

Mar 4 Loach's Path

.jpg)

Mar 4 Loach's Path

Mar 5 Bioski

Mar 5 Bioski

Mar 6 Moonlight

Mar 7 Saturday am run

Mar 9 Bioski

Mar 9 Bioski

Mar 9 Bioski

Mar 9 Moonlight Bridge

|

|

Upcoming Events

|

May

24, 2026

SudburyRocks Race,

Run or Walk

|

Registration is now open for 2026

SudburyROCKS!!! Can you feel the excitement! Secure

your spot now, and mark your calendars for another

epic event, Sunday May 24th 2026. We can’t

wait!

Click on the Race

Roster link in the bio or below!

https://raceroster.com/events/2026/111700/sudburyrocks-2026

Early bird prices

until December 31st.

|

|

|

HOME

| ABOUT US | CONTACT

| ARCHIVES | CLUBS

| EVENTS | PHOTOS

| RACE RESULTS | LINKS

| DISCUSSION

|